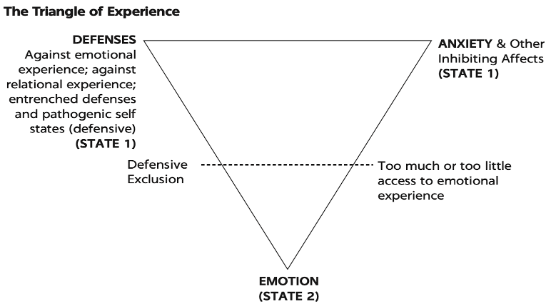

This is the second instalment of a 3-part series in which we look at the Triangle of Experience tool and how it can help us make sense of our emotions.

Last month we explored Feelings & Emotions, and you can read the article here.

Subscribe to our newsletter to have these posts delivered straight to your inbox.

Part 2

Anxiety & Distress

All of us struggle with anxiety at times. But many are not quite sure how to work with it. The Triangle of Experience offers one of the most simple and effective tools that help demonstrate how we can both better understand and change our approach to anxiety, as well as the underlying emotions we likely are experiencing.

Anxiety is a feeling of worry and/or fear that we all experience at various times in our lives. It’s a natural human response to potentially threatening situations. But it can become a problem when we negatively react to experiences that aren’t particularly dangerous, such as the fear we can develop of our feelings.

Our core feelings, meaning the feelings that are likely arising inside of us, are represented on the bottom point of the Triangle of Experience, and this was the focus of last month’s article. The upper righthand corner represents the anxiety, fear and distress that, through our early experiences with our caregivers, became associated with our core emotions, needs and desires. For simplicity’s sake, these are labeled as anxiety on the triangle but in reality they are a number of different inhibitory feelings, including fear, shame, guilt, and distress.

If we’ve learned early in life that any of our core emotions, needs, or desires are likely to cause a negative reaction in others, namely our caregivers, they become associated with a sense of threat and our amygdala sounds the alarm that danger is drawing near. In turn, our nervous system gets activated and our body responds with feelings of discomfort. These physical sensations are usually the first sign that our nervous system is reacting as though we’re in danger. It’s telling us we’re starting to have an emotional experience that’s making us uncomfortable. Our sense of threat is trying to get our attention and get us to do something to avoid perceived danger. And the suffering and discomfort that gets generated makes us want to put an end to the experience we’re having, make it go away.

Sometimes, the fact that we’re getting uncomfortable (the anxiety corner of the Triangle) makes it obvious that we’re entering this anxiety phase, as there are plenty of ways in which anxiety shows up in our bodies. Our muscles get tense or twitch, our heartbeat quickens, we feel a sense of edginess, restlessness and agitation. We may also experience an ache in our stomach, sweaty palms, an urge to urinate, dizziness, numbness, tingling sensations, or a desire to flee or withdraw from the situation we’re in.

At other times our symptoms can be more subtle. Anxiety can sneak under the radar and go unnoticed, especially when we are not attuned to our physical experience. We might feel a slight sense of uneasiness. A faint flicker of energy in our chest, a quick twitch in our stomach. These sensations are distant echoes of past distresses reverberating from the deep recesses of our mind, body and spirit.

Changing your approach to anxiety

When you notice the feelings of anxiety, try naming the experience when you’re triggered, as this will help reduce your anxiety. As psychiatrist Dan Siegel is fond of saying, “name it to tame it.” So, say to yourself: ‘I’ve been triggered’ or ‘a young part of me is feeling anxious’ or something along those lines. Make sure that whatever label you assign is short and to the point. Then, note that your anxiety is likely telling you that there’s a deeper emotion at hand, one that needs your attention.

To get acquainted with how your emotion related anxiety shows up for you, try this Anxiety Awareness Exercise:

Find a quiet place where you won’t be interrupted and can tune in to what’s going on inside of you. Sit upright with your back straight and your feet flat on the floor. Close your eyes and give yourself a moment to settle down before you focus inwardly by taking a few deep breaths and observing your inhalation and exhalation without trying to change anything.

As you sit there, think of a time with your partner, family member, or friend that brought you to the edge of your emotional comfort zone. Perhaps a time you openly shared your sadness, disappointment or hurt with them, or a time of conflict in which you considered or actually gave voice to your anger or frustration at something they did or said.

Imagine getting ready to express yourself, leaning into the experience and paying close attention to what’s happening in every area of your body: your head, face, neck, shoulders, back, chest, arms, stomach, legs. Notice if there’s discomfort, perhaps tightness or tingling. Do certain areas feel warm or cold? Just observe your experience without looking to change it. When you’re done, take a deep breath and let it go. Feel it leave your body and come back to center. If you can, take a moment to write down the physical sensations you observed during the exercise.

If you experience physical sensations you weren’t aware of before, that’s a great sign, as it shows you are developing awareness of your felt experience. But it doesn’t matter if you don’t notice anything at first. That’s okay, too. Every time you turn your attention inward, no matter what you find, you’re growing your observation skills and expanding your awareness. And the more you do it, the better you’ll get at it, and the more you’ll notice.

Make it a practice to tune into your felt experience throughout your day. Scan your body from head to toe and see what sensations you notice and feel. Doing so will help you build your awareness of and connection to your inner experience and help you discern when anxiety signals are showing up.

A case study

Everyone has their own triangle of experience as it relates to particular emotions and situations. Here’s an example taken from my book Living Like You Mean It, that shows how the triangle illustrates the experience of someone I’ve called Julie for the sake of the exercise.

Julie shares good news of a new job with her father. But instead of celebrating with her, he reacts with doubt and concern. He questions her ability to handle the new role and she starts to feel angry toward him (the E point on the triangle). But afterward, Julie starts to feel uncomfortable and doubts herself. Julie is largely unaware that her anger, a feeling that was responded to poorly in her family when she was a child, is causing her to feel anxious and uncomfortable. It just happens and she gets caught up in a swirl of anxiety and doubt. Unconsciously, Julie feels conflicted about the anger she feels. Her nervous system responds as though it’s dangerous for her to feel this way and becomes anxious and uncomfortable (the ANXIETY point on the triangle). This leads to her unknowingly resorting to her usual defenses of doubting herself to help her cope with these feelings and emotions (the DEFENSES point on the triangle that we will focus on next month).

The key thing to remember here is that the more Julie tunes in to her emotional experience when she is triggered, and the more she practices emotional mindfulness, the more aware of the cause of the discomfort she will become. Then she can learn to attend to her anger, feel less afraid of it, and find a way to make constructive use of it.

We’ll get into the next steps in the following editions of the newsletter, but if you’d like to learn more about the stages involved in practicing emotional mindfulness, and look at the Triangle of Experience in more detail, see my books, Loving Like You Mean It and Living Like You Mean It.